What can we say to a famous children’s author, facing Alzheimer’s diagnosis, who is contemplating assisted suicide?

By: Dave Andrusko, originally published September 24, 2025, National Right to Life

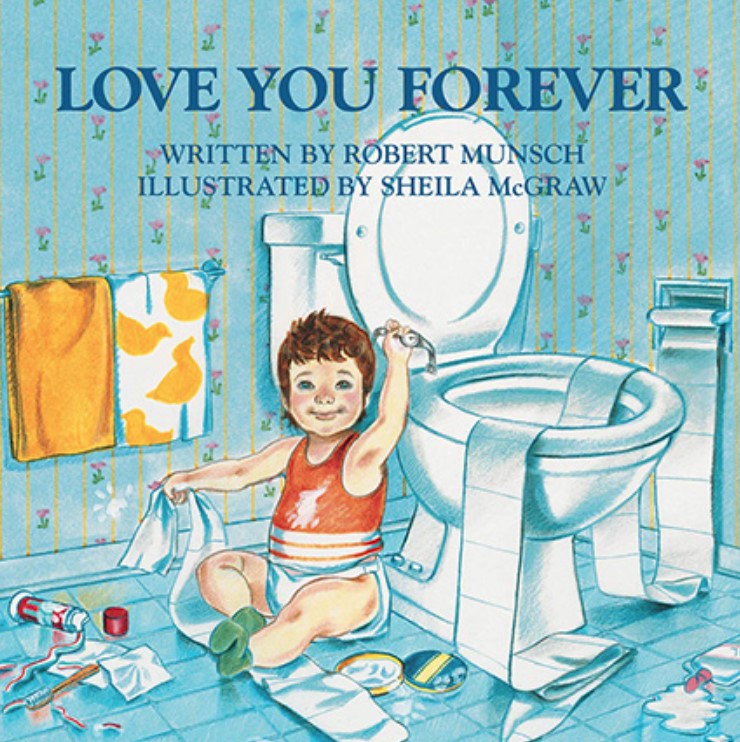

Back in 2014, Rai Rojas wrote a deeply touching story titled “The story behind ‘I’ll love you forever, I’ll like you for always,’ Robert Munsch’s classic children’s story.” All of us who have read Munsch’s story can identify with the almost irresistible need to weep.

If you recall, as Leah Savas of World magazine reminds us today,

The book begins with a mother rocking her baby and singing to him, “I’ll love you forever / I’ll like you for always / As long as I’m living / my baby you’ll be.” It shows her doing this through various stages of the boy’s life until their roles reverse at the end of the book. The final pages depict the now-adult son holding his frail, old mother and singing her a different version of the same song: “I’ll love you forever / I’ll like you for always / As long as I’m living / my Mommy you’ll be.”

But Rai quoted from Munsch’s webpage which explained the book’s backstory:

“I made that up after my wife and I had two babies born dead. The song was my song to my dead babies. For a long time I had it in my head and I couldn’t even sing it because every time I tried to sing it I cried. It was very strange having a song in my head that I couldn’t sing.

“For a long time it was just a song, but one day, while telling stories at a big theater at the University of Guelph, it occurred to me that I might be able to make a story around the song.

“Out popped ‘Love You Forever’ pretty much the way it is in the book.”

It moves me even today, as I thought back on reading it to my children. I recommend you read it before you read of the devastating news that facing an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, Robert Munsch says he is contemplating assisted suicide.

“Hello, Doc — come kill me!” the Canadian citizen joked to the New York Times. “How much time do I have? Fifteen seconds!”

Munsch was interviewed by the New York Times’ Katie Engelhart. The title of her profile (as you read it, you come away thinking that perhaps it was as much for her as her readers) was “When Dementia Steals the Imagination of a Children’s Book Writer.”

Savas points her readers to a profoundly moving story written following the Times’ profile by Amanda Achtman at Public Discourse. The title is “Will You Love Me Forever?”

It is critically important to know that Achtman “has worked on Parliament Hill in an effort to prevent the expansion of euthanasia to persons with living with disabilities or mental illness. Amanda works with Canadian Physicians for Life and teaches Catholic Bioethics at End of Life at St. Bernard’s School of Theology and Ministry.” She knows of what she speaks.

Love you forever “is a touching story of the natural circle of life and of the unconditional love for which we are made,” Achtman writes. “This is one reason why many Canadians are shocked that the book’s author, of all people, is saying he wants a doctor to end his life by euthanasia.”

“I have worked hard to overcome my problems, and I have done my best. I have attended twelve-step recovery meetings for more than 25 years,” Munsch wrote in a note to parents on his personal website. “My mental health and addiction problems are not a secret to my friends and family. They have been a big support to me over the years, and I would not have been able to do this without their love and understanding.”

Engelhart’s article, Achtman writes, “then fixates on what Munsch can no longer do. He can no longer ride a bike, drive a car, and, particularly cruelly for an author, he can no longer read. Like the mother in his classic story, he himself has become old and sick. But, unlike her, he now is tempted to seek state-sponsored suicide.”

Achtman observes, in a way, how readers are let down (to put it selfishly) by “schedul[ing] his death at the hands of a physician” which “would contradict the message of unconditional love that he shared all those years ago, a message that resonated with hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of children and parents.”

But she makes us understand how suicide, assisted or otherwise, “would also contradict the support and understanding with which, thankfully, he was met throughout his life.

When he faced depression and suicidal ideation, he got a psychiatrist. When he struggled with drugs and alcohol, he joined Narcotics and Alcoholics Anonymous. After he lost two children, he and his wife welcomed three through adoption. But now that he is elderly and asking for euthanasia, what is on offer? Why, only now, should there not be any antidote?”

It turns out that Munsch’s thoughts are not new, according to one of his children. He “discussed this with journalists four years ago upon receiving diagnoses of dementia and Parkinson’s.”

Now, in The New York Times interview, he is admitting his deepening insecurities over having dementia, expressing his fear about becoming “a turnip” or “a lump.” The request for medical assistance in dying (MAiD) is a cry of the heart concerning self-worth and lovability. Now that he can no longer tell stories, which had always been such a key part of his identity, he is shaken and vulnerable. The request for euthanasia betrays a fundamental lack of self-esteem.

But, bringing us full circle, Achtman writes that Love You Forever, his most famous book of all,

was actually inspired by the two children that he lost. On his personal website, Munsch’s biography says that he wrote Love You Forever as a memorial for his two stillborn children, delivered in 1979 and 1980.

In a tragic way, these were

gifts that completely transformed him, that made him a father, that broke open his heart to that radical “Love You Forever” kind of love. These two children who never took a breath in this life have had an incalculably positive impact on the world by inspiring Munsch to write his book and encouraging readers to love one another, despite failures and weaknesses, through every season of life.

Achtman’s conclusion reminds us of our fundamental interdependence, whether we are unborn children or very old and frail:

No matter what he suffers now, Robert Munsch will never be more vulnerable, more discreet, more unspoken than his stillborn children who inspired his bestselling book of all. In the universality of Robert Munsch’s fears about dementia, we see the need to propose something other than death. It is time for someone else to continue the story with him still in it. Just as in the story, he needs someone to pick him up and rock him “back and forth, back and forth, back and forth.” Singing over him: “I’ll love you forever / I’ll like you for always/ As long as I’m living / My [dear one] you’ll be.”

If stillborn children could inspire one of the most-loved children’s books in the twentieth century, then maybe a grandpa with dementia will inspire one of the best stories in the twenty-first.

Dave Andrusko is Editor at National Right to Life News.