Rapid Fertility Decline Is an Existential Crisis

By: Jesús Fernández-Villaverde, originally published February 11, 2025, American Enterprise Institute – AEI.org

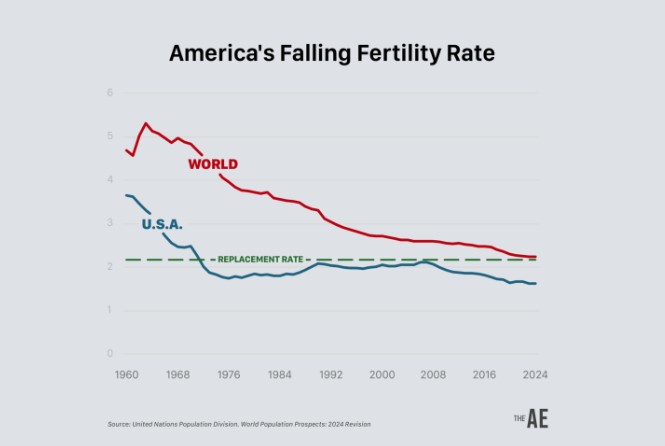

Humanity has entered a new era of rapid population decline. Globally, the total fertility rate is likely already below replacement—that is, below the level needed to sustain the population in the long run, approximately 2.18 children per woman. In the US, it’s around 1.6 – without immigration, our population would have already begun to decline. If we are unable to address our fertility crisis, the US will face an existential economic crisis driven by a steep decline in fertility rates—one that could have an impact measured in the quadrillions of dollars.

Being “below replacement” does not mean global population will immediately stagnate. Due to a phenomenon known as population momentum, growth will continue for approximately 30 more years. Current world births are temporarily high because large cohorts of women born in the late 1990s and early 2000s are now having children while their parents are still alive. However, all of today’s global population growth is a solely a result of this momentum.

Few countries remain above replacement—except for those in sub-Saharan Africa and Central Asia. Furthermore, fertility rates are declining more significantly and, importantly, at a faster pace than anyone anticipated a few years ago. This trend is evident in both wealthy and poor nations, in religious and secular states, in countries with right-wing governments, as well as those with left-wing governments, and in nations with free abortion access and those with restrictive abortion laws. Pick any country at random from a world map, and the chances are high that its fertility rate is falling rapidly.

In the Americas, from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, only Haiti, Honduras, Bolivia, Paraguay, and a handful of small Caribbean nations are on pace to exceed replacement levels in 2025—and only slightly. The region’s demographic giants—the US, Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, and Canada—are already significantly below replacement. Notably, as of early 2025, the US has a higher fertility rate than Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, and Canada.

In Asia, countries like China, India, Japan, Vietnam, Thailand, Turkey, Iran, and South Korea—among many others—are all significantly below replacement levels. In China, Japan, South Korea, and Thailand, deaths currently outnumber births; these countries have exhausted their momentum, resulting in population decline. At the present rate, China could lose as many as 600 million inhabitants by the end of the century.

Sub-Saharan Africa presents a less clear picture, as data quality is poor (many of the UN’s figures are based on estimates). Nevertheless, some signs suggest that fertility is declining there as well. Three weeks ago, an economist from Ghana told me, “Nobody in my village is having kids anymore.” The plural of anecdote is not data, but his observation aligns with other indicators.

Currently, the fertility rate in the US is around 1.6, significantly below the replacement rate of 2.1. (Note that the global replacement rate of 2.18 is slightly higher than that of the US due to selective abortion of girls in Asia and higher female mortality in Africa). This issue is not new; the US has been below the replacement rate since the 1970s, although the recent decline in fertility is unprecedented. In fact, without the influx of immigrants (like yours truly) and their US-born children, the US population would likely have started to decline a decade ago.

The implications of declining fertility in the US are the most crucial economic issue of our time.

Consider the fundamental accounting equation for economic growth. Output growth is equal to the growth rate of output per worker (a measure of productivity) plus the growth rate of the labor force. Since the Civil War, the long-term average growth rate of output per worker in the US has been approximately 1.9% annually. This rate has occasionally been higher (as seen in the 1950s and 1960s) and at other times lower (as observed in the 1970s and 2010s). However, deviations from this historical average have generally not been significant.

Therefore, when the number of workers increased by about 1% annually, US economic growth remained around 2.9% per year. During strong years—particularly during economic expansions when productivity surged—the economy achieved growth rates of 4% or more. In weaker years, when productivity slowed or fell, output grew by only 1% or 2%. Total output only shrank for an entire year on rare occasions.

Fast forward to the 2040s, when the growth rate of workers may be -1% per year. Even if we maintain the output per worker growth rate at 1.9% (a big if), the economy will grow at a meager 0.9% annually. In prosperous years, we could reach 2%; in downturns, the economy will contract, not just grow more slowly.

Is this an unlikely scenario? Unfortunately, no. We have already witnessed it—it’s called Japan.

Between 1991 and 2019, Japan’s GDP grew at an annual rate of 0.83%, significantly lower than the US rate of 2.53%. The main driver of their weak economic performance? Japan’s dramatic demographic collapse.

Between 1991 and 2019, a combination of past low fertility and population aging led to a 0.54% annual decline in the number of working-age adults. Total hours worked fell at a similar rate of 0.43% per year; the gap between these figures reflects increased labor force participation among older workers and women.

In contrast, the US, bolstered by higher fertility rates and significant immigration, experienced an annual growth of 0.91% in its working-age population, with total hours worked increasing by 1.04%. Consequently, Japan’s GDP per working-age adult grew at a rate of 1.39% per year, compared to 1.65% in the US—a relatively minor gap. When measured by output per hour worked, Japan’s growth was at 1.26% per year, while the US recorded 1.53%.

Excluding the early and middle 1990s, when Japan was engulfed in the aftermath of its real estate bubble, Japan’s growth per working-age adult from 1998 to 2019 outpaced that of the US

Japan’s weak economic performance over the past 25 years is not a mystery; it is merely the result of a declining population. Demographics shape destiny, even in terms of economic growth. In other words, Japan’s current economic situation (good performance of growth per working-age adult but poor total output growth) foreshadows the future of the US economy.

The consequences of significantly slower output growth will be severe for the US economy. While we consider output growth per capita when assessing welfare (and output per capita growth will not decline as sharply as total output growth), total output growth is crucial for addressing the funding of Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, servicing our public debt, and financing our armed forces in the face of increasing international competition. Once we begin to contemplate the fiscal implications of a declining population, it becomes difficult to focus on anything else.

When I reach this point in seminars, lectures, or media interviews, I invariably receive three questions: climate change, immigration, and artificial intelligence.

Isn’t a declining population good news for the environment and climate change?

Paradoxically, no. A stable or slowly declining population can help ease pressure on the environment and facilitate the transition to net-zero CO2 emissions. However, a collapsing population, like the ones we are likely to encounter given current fertility rates, will generate so many fiscal problems that there will be no room left in government budgets for environmental concerns.

This is not mere speculation. The current economic challenges facing many European economies primarily arise from the rapid increase in spending on social security and healthcare for the elderly, which has overshadowed other budget priorities. In democracies where the median voter is older, there tends to be less emphasis on long-term environmental issues and ensuring social security payments. While this may be a sobering view of human nature, it is grounded in historical experience.

Why not just bring more immigrants?

Surprisingly, the answer is no.

The US has a welfare state. This means that those individuals who are below 60th percentile or so of the income distribution are net receivers of funds from the government during their lifetime (i.e., the net present value of what they contribute less than what they receive later in life, like Social Security and Medicare), those between the 60th and 90th percentile are approximately net zero contributors, and only at the top 10th percentiles are net contributors. In other words, all immigrants that come to the US are below the 90th percentile and won’t help solve the fiscal woes created by low fertility. European countries that have the detailed databases required to compute these numbers carefully have found that not even the second-generation (i.e., the sons of immigrants born in the country) is a net contributor to the welfare state.

We need to assess immigration policy based on various factors in addition to its fiscal implications. My argument is more modest: “If you think that raising the number of low- and middle-skill immigrants will solve the long-term fiscal issues facing the US, you are mistaken.”

Won’t artificial intelligence (AI) really solve all of this?

This is my favorite question to answer, both because it reflects the widespread misunderstandings about AI among the public and because much of my academic research focuses on AI. Again, the answer is no. The key is something called the Moravec’s Paradox.

Pick any freshman at the University of Pennsylvania at random and ask them to solve a system of partial difference equations, a mathematical model illustrating how multiple interconnected quantities change continuously over time and space, describing phenomena like the weather or demographics. The freshman will likely find this task overwhelming. In fact, even most graduate students in applied mathematics and natural sciences struggle for years with it. However, AI can solve this system effortlessly.

Now, ask the same freshman to make their bed or clean their dorm room. They can do that, albeit grudgingly, like most teenagers, without any problem. We are not even close to having a robot with AI that can make beds or clean dorm rooms outside of experimental and well-structured test cases.

This is Moravec’s Paradox: programming computers to perform tasks that most humans consider very difficult (e.g., advanced math) is much easier than programming them to carry out tasks that most humans find trivial (e.g., making a bed). Unfortunately, the problems we will face due to the falling population, such as the need for old-age care, require skills like making a bed and not doing advanced math.

So, what can the US do to address the fertility crisis?

This is the one-quadrillion-dollar question (yes, tackling fertility has an impact measured in discounted terms of quadrillions of dollars, not just small change like a miserly trillion dollars here or there). We remain uncertain. We know, for example, that offering tax breaks for fertility doesn’t seem to make much difference.

Instead, marrying more people (and doing so earlier) does appear to be significant. The US should restructure its entire economic policy toward a family-oriented approach that facilitates marriage. Highlighting the main components of such a policy would merit an article in itself. However, it encompasses housing affordability, reforming the educational system, and enhancing the labor and social skills of many young men.

Returning to the topic of climate change, many young people are deeply concerned that we face extinction due to this issue. While I share the concern about climate change, it’s not at the level of urgency of our fertility crisis: we have already developed the technologies needed to transition to net zero emissions. The current challenge lies mainly in political implementation. This will require effort and may lead to more damage to the planet than what an ideal policy would have caused, but I believe we will achieve this goal. The true economic challenge of our time, for humanity overall and the US specifically, is the fertility crisis. Let’s get to work on it—as soon as possible.

Jesús Fernández-Villaverde is the John H. Makin Visiting Scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, where he studies macroeconomics, econometrics, and economic history.

Main Image Credit: The American Enterprise.