An Impending Population Crisis? World Fertility Rate Hits 60-Year Low

By: Sylvia Xu, originally published September 19, 2025, The Epoch Times

The decline in fertility, which began in the 1960s, coincided with societal change including rising divorce rates and legalized abortion.

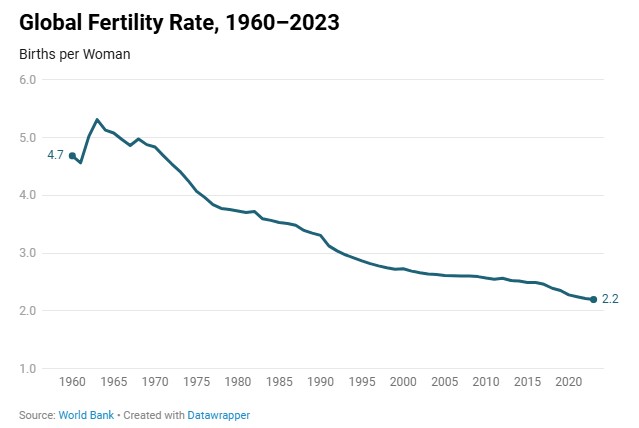

Fertility rates have plummeted worldwide over the past six decades, leading experts to warn of dire consequences as the downward trend continues.

Continued low fertility rates will cause “a gradual implosion of the world’s economy as the population ages and dies,” Steven Mosher, president of the Population Research Institute, told The Epoch Times in an email. Mosher is an expert on population control, demography, and China.

“This will not occur overnight, of course, but once it is well underway it will be difficult, if not impossible, to reverse course,” he said.

Fertility rates (the average number of children born to a woman in her lifetime) are different from birthrates (the number of live births per 1,000 people in a population over a given period), although the terms are related and often used interchangeably.

Countries with low fertility rates are also likely to have low birthrates.

Macroeconomist Jesús Fernández-Villaverde called low fertility rates “the true economic challenge of our time,” in a February report for the American Enterprise Institute.

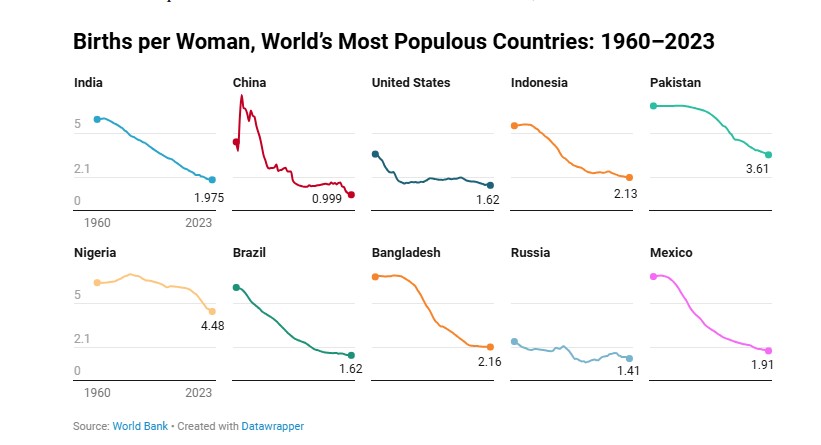

In 1960, the average woman bore four or five children in her lifetime. By 2023, that number had halved to 2.2, approaching 2.1, the replacement level—or the level at which a population replaces itself from one generation to the next.

In July, the U.S. Census Bureau projected that the world’s population will reach 8.1 billion this year. Experts say although the figure has grown from 3 billion in 1960, the number to watch is the pace of population growth.

The bureau stated that “the rate of growth peaked decades ago in the 1960s and has been declining since and is projected to continue declining.”

Fernández-Villaverde warned that while the sagging rate of growth may not have immediate consequences, in less than half a century, declining fertility will impact the world economy. Countries with low or negative birthrates will contend with a shrinking workforce and the ballooning costs associated with an aging population.

Global Fertility Rates

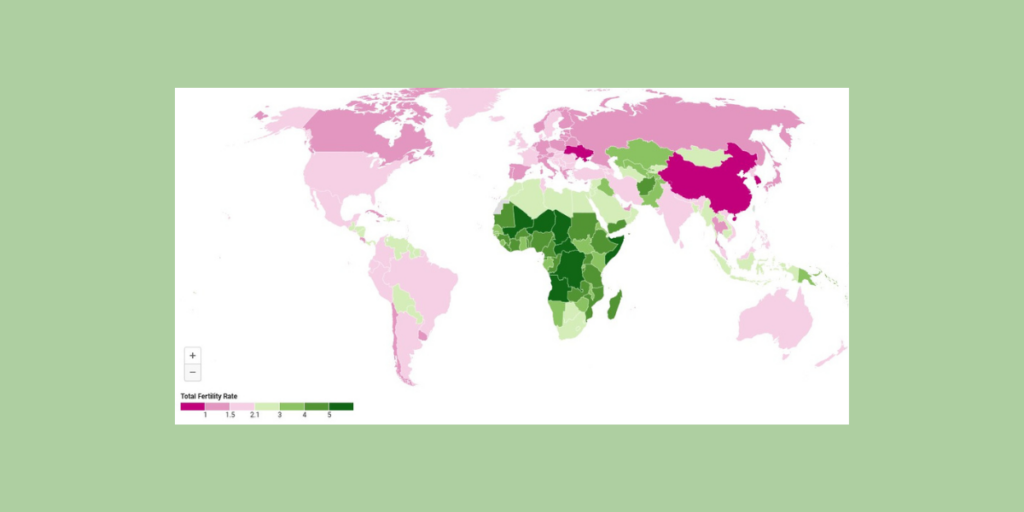

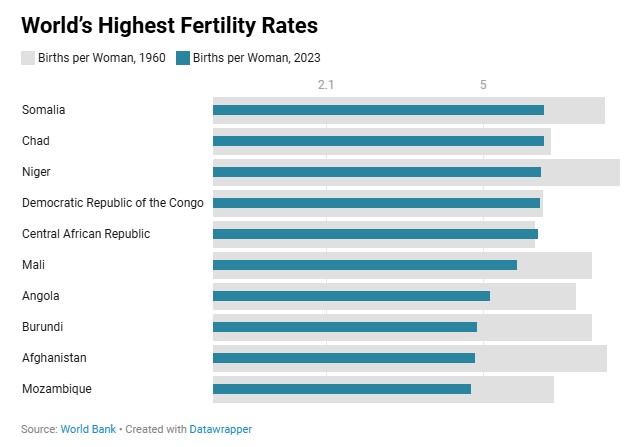

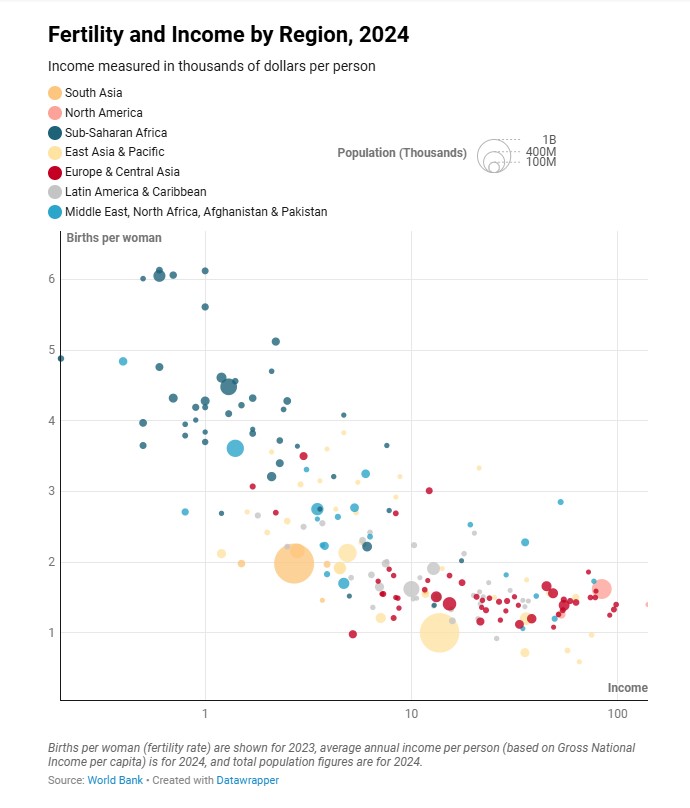

Only about 4 percent of the world’s population reside in a country with a high fertility rate—more than five children per woman—and all of those nations are in Africa, the Census Bureau noted. Even in those countries, fertility rates are generally lower than they once were.

The bureau reported that nearly three-quarters of the world’s population live in countries where fertility rates are at or below the replacement level.

The fertility rate in India, the world’s most populous country, has steadily declined over the past six decades. In June, the UN Population Fund reported that India’s fertility rate stood at 1.9 children per woman, down from five or six children in 1960.

In 1990, China’s fertility rate was 2.51, despite its one child policy. By 2023, it had dropped to less than one birth per woman, according to the United Nation’s population division.

In the United States, fertility has undergone a persistent decline. It fell below the replacement level in 1972 and reached 1.62 in 2023, a historic low.

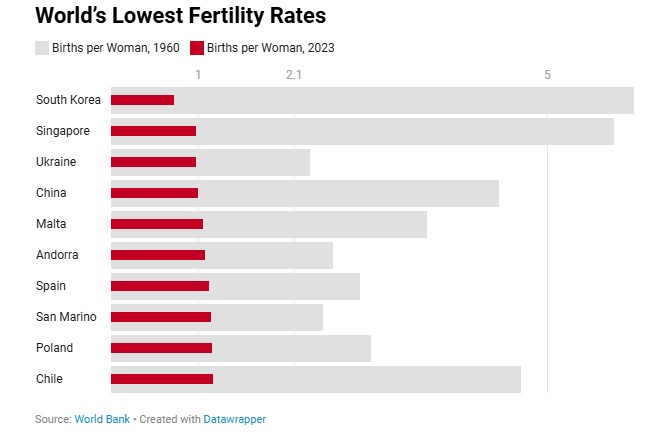

Asian and European countries have the lowest fertility rates in the world, and South Korea (0.72), Singapore (0.97), Ukraine (0.977), and China (0.999) all have rates below one.

Across much of Europe, North America, and Eastern Asia, fertility rates have fallen below replacement level.

Looking Back to the ‘60s

In the Western world, the decline in fertility rates that began in the 1960s coincided with the advent of oral contraception, the legalization of abortion, and the widespread adoption of no-fault divorce.

In the United States, the first oral contraceptive was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1960. Within five years, the birth rate in the United States had already declined “substantially,” a report from the National Fertility Study indicated. By 1976, the U.S. fertility rate had fallen to a record low of 1.7.

In 1973, abortion became legal in the United States following the Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade. At the time, a handful of other countries had also legalized abortion, including the UK, Norway, and Singapore.

The United States’ decision was followed by several countries including Denmark, South Korea, France, West Germany, New Zealand, Italy, and the Netherlands. Today, only 22 countries completely ban abortion.

Research indicates that abortion legalization led to a significant drop in birth rates.

Shortly after Roe v. Wade, live births dropped by one-third in upstate New York, according to a 1975 study published in the International Journal of Epidemiology.

Fertility rates on average dropped 4 percent in the United States after abortion was legalized, a 1999 study of individual states published in the American Journal of Public Health found.

A study by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, conducted after Mexico City legalized first-trimester abortion in 2007, offered a more recent look at the connection between abortion and declining fertility.

The Mexico City Federal District—with a population of about 8.8 million in 2007—was the first of Mexico’s jurisdictions to legalize abortion. The effect of the city’s legislation on women in their 20s was “pronounced,” the study’s authors concluded. “We estimate that abortion legalization reduced the number of births in Mexico City by an additional 4 percent.”

In 2023 the country’s supreme court decriminalized abortion nationwide. .

In another example, a report in the peer reviewed journal PLOS One concluded that after abortion was legalized in Nepal in 2002, “total fertility … declined by nearly half, despite relatively low contraceptive prevalence.”

Data from Nepal’s Demographic and Health Survey indicate that from 2001 to 2011, the total fertility rate dropped from 4.1 to 2.6.

The Nepal study found that not only did the country’s total fertility rate drop, “desired fertility declined” as well.

In line with that, the National Bureau of Economic Research said in a 2004 report that the decline in births following abortion legalization is a permanent effect.

“Much of the reduction in fertility at the time abortion was legalized was permanent in that women did not have more subsequent births as a result,” the report concluded, noting an increase in the number of women who remained childless.

The Guttmacher Institute estimates that more than 63 million abortions were conducted in the United States between 1973 and 2021. Worldwide, 73 million abortions are conducted per year, according to the World Health Organization.

Additionally, several studies have drawn a connection between skyrocketing divorce rates and shrinking fertility rates.

In the late 1960s, divorce rates shot up in Western countries as divorce law reforms made it easier for couples to end marriages without proving one partner was at fault.

A study published in the journal Labour Economics in 2014 concluded that “the introduction of divorce law reform decreases fertility rates, and that the effect appears to be permanent.” That study was conducted across 18 European countries, spanning the period 1960 to 2006.

The Decline in the East

In China, as many as 40 million people died of starvation during the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) Great Leap Forward campaign from the late 1950s to the early 1960s.

Additionally, around 7.73 million Chinese were killed in the subsequent Cultural Revolution campaign from 1966 to 1976.

Despite the death toll from these campaigns, China enacted a one-child policy in 1979, accompanied by mandatory contraception, sterilization, forced abortion, and even infanticide. China claimed the policy prevented 400 million births between 1979 and 2011.

The impact may have been even greater. A 2017 paper in the journal Demography by Daniel Goodkind, an analyst at the Census Bureau, writing about the “astonishing impact of China’s draconian policy choices,” estimated that China’s one-child policy had actually “averted” as many as 520 million people as of 2015, with a much greater future impact due to “demographic momentum.”

Economic Concerns

Today, economic concerns such as the high cost of housing and childcare are often cited as factors in declining fertility rates.

In South Korea, which has both a strong economy and the world’s lowest fertility rate, a United Nations survey indicated that “financial limitations” were the main reason for the country’s record-low births.

In the survey, 58 percent of respondents cited financial limitations as obstacles to parenthood—12 to 19 percentage points above the worldwide average. In the highly urban nation, nearly one-third said they faced housing challenges, such as lack of space or high costs for homes and rent. Twenty-eight percent cited childcare as an issue.

In the United States, a July 2024 Pew Research survey found that among adults aged 18 to 49 who don’t have children, 36 percent said they couldn’t afford to raise a child.

In another 2024 survey conducted by The Harris Poll for NerdWallet, more than 1 in 5 of 2,000 U.S. parents of children under 18 said they didn’t plan to have another child because it would be too expensive. Twenty percent of respondents called childcare their most significant financial stress.

The Department of Labor says childcare is prohibitively expensive for many Americans. In 2022, the annual cost for a child’s full-day care ranged from $6,552 to $15,600, or 8.9 percent to 16 percent of median household income.

In certain counties, the median cost of center-based child care exceeded the national median of $15,216 for annual rent in 2022.

Income and Family Size

Despite financial concerns, cultural and religious factors have more of an impact on fertility rates than income levels, according to Lyman Stone, senior fellow and director of the Pronatalism Initiative at the Institute for Family Studies.

His 2024 analysis suggests that “there is no cross-culturally stable impact of income on fertility,” despite what he calls “the common stereotype that poor people have more babies than rich people”—a stereotype borne out by high fertility rates in sub-Saharan African nations with low income.

Stone’s research indicates that high-income black and Hispanic women in the United States tend to have fewer children, while high-income white women tend to have more children than white women at lower income levels.

Foreign-born women in the United States have higher fertility rates at every income level, showing little connection between income level and fertility.

Meanwhile, Amish and ultra-Orthodox Jewish women in the United States average approximately double the amount of children as other American women, no matter what their income.

Current Factors in Fertility Decline

A host of other factors affect decision making about family size.

Access to schooling and job opportunities for women often leads “to delayed marriage, postponed childbirth, and smaller family sizes,” said Kent Smetters, professor of business economics and public policy at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. Smetters calls this factor “by far the biggest” when it comes to falling fertility rates.

In China, despite more relaxed policies meant to encourage childbearing, studies show that women are still reluctant to have babies. In 2015, the Chinese regime relaxed its one child policy for the first time: two years later, births had actually fallen by 3.5 percent, according to Chinese state media.

In a May 2017 survey of 40,000 working women in China conducted by Zhaopin, a recruitment agency, about 40 percent of childless women surveyed said they did not want children, while nearly 63 percent of working mothers with one child said they did not want another child. Those surveyed cited lack of time and energy, finances, and career concerns.

Nearly 40 years of anti-natal propaganda have had a corrosive effect on attitudes towards children and childbearing in China, Mosher said.

“Not to mention that the sex-selective abortion and infanticide of millions of unborn and newborn baby girls has reduced the number of young women in China—to the point where every young women would have to marry in their early 20s and have three children to offset the population decline,” he said.

After telling young people in China for decades that “the fewer children you had, the better off the country would be, the better off they would be,” Mosher said in a 2023 interview with Parousia Media, “their propaganda had been very effective.”

Finally, there are intangible factors limiting family size.

A June study of almost 1,500 adults commissioned by Population Connection found that about 30 percent of respondents said “overpopulation and climate change” made them uneasy about having children.

White House Efforts

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act, signed by President Donald Trump in July, includes provisions to support new families, including financial grants for newborns and an expanded child tax credit.

The bill creates savings accounts for children born between 2025 and 2028, seeded by a federal government deposit of $1,000. Parents and others can add up to $5,000 per year in after-tax dollars before the beneficiary is 18. Employers can contribute up to $2,500. Money in the account grows without being taxed, while withdrawals for approved uses are taxed at a lower rate.

The new bill also provides more tax relief for families with children under 17. The federal Child Tax Credit will increase from $2,000 to $2,200 per child in 2025 and will be adjusted for inflation going forward.

Even families who owe no income tax can receive up to $1,700 per child as a tax refund for the 2025 tax year. In February, Trump signed an executive order aimed at expanding access to in-vitro fertilization (IVF) and reducing out-of-pocket and health plan costs for the treatments.

“My Administration recognizes the importance of family formation, and as a Nation, our public policy must make it easier for loving and longing mothers and fathers to have children,” the president said.

Efforts Across the Globe

In France, eligible families can receive at least 1,080 euros (about $1,300) for each birth. Families can also have up to 85 percent of childcare costs covered for children under 6.

Italy offers a one-time grant of 1,000 euros (about $1,100) for each child born or adopted after Jan. 1, 2025. It also offers a bonus to cover the costs of childcare. It provides a monthly allowance for families with dependent children of between 50 and 175 euros per child (about $60 to $200), plus additional benefits for mothers under 21 as well as kindergarten vouchers.

Seoul will spend about $2.3 billion in 2025 to boost births by expanding housing support for families with newborns, offering public housing and additional benefits to newlyweds and larger families, increasing emergency and 24-hour childcare access across the city, and hosting matchmaking events for singles seeking partners. Gyeonggi Province, where Seoul is located, is also experimenting with a shorter work week, in response to concerns that South Korea’s intense work culture is impacting fertility rates.

Singapore’s bid to boost births includes a plan co-funded by the government that covers up to 75 percent of the cost of fertility treatments at public hospitals for eligible couples. The government also offers a grant of $5,000 for babies born after April 1, 2025.

Japan’s Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru has called his country’s declining fertility a “quiet emergency”—the country’s fertility rate fell to a new low of 1.15 in 2024. In a policy speech in January, Ishiba announced measures to address the slump.

Key initiatives include raising childcare leave benefits to 100 percent of take-home pay for both parents, increasing wages, and aiming for a 1,500 yen ($10.20) per hour minimum wage by the late 2020s.

Sylvia Xu is an author at The Epoch Times.