The Fallout from Ohio’s Abortion Law

By: Jack Butler, originally published February 20, 2025, National Review

Hope remains for reviving the culture of life

Marty Martin wasn’t the only Ohioan who felt like he got a “punch in the gut” on November 7, 2023. Nearly a year later, in October 2024, the Steubenville teacher and thousands of other pro-lifers (including some of his students) converged on Capitol Square in Columbus for the Ohio March for Life. It was the third iteration of the event, which began after the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision permitted states to regulate abortion. And it was the first since what Kate Makra, executive director of Cleveland Right to Life, similarly described as the “gut punch” of the state’s decisive vote in favor of enshrining a right to abortion in the state’s constitution.

The Ohio march was well attended on this sunny Ohio fall day. In the shadow of the state’s undomed capitol, a vast array of pro-lifers — from legislators to veteran activists to students at the state’s many Christian schools — had come to remind Ohio that “WE’RE. STILL. HERE,” as one of their many chants that day went. Their resolve is undaunted. But with a right to kill the unborn now constitutionally prescribed, Ohio pro-lifers are trying to make sense of how that happened, what it means for abortion now, and what they can do to continue their worthy fight.

Why did 57 percent of Ohio voters support a pro-abortion amendment? When I spoke to some of these same pro-lifers shortly before the election, they had some concerns about the asymmetry, in money and media, between their effort against Issue 1 and the forces working for it. And that asymmetry did manifest: the pro-abortion side spent nearly $60 million, much of it from out of state, while the pro-life side spent about $36 million. But they were confident that Ohio pro-lifers were moving in concert. Margie Christie, executive director of Dayton Right to Life, believes this remained true of the effort throughout. “I thought we did a good job of unifying as a state and all saying the same things,” she says.

Having more resources enabled the pro-abortion side to amplify misleading claims about how voting no on Issue 1 would affect miscarriage care (despite a clarification to the contrary issued by the Ohio Department of Health before the vote). But it would not have resolved a fundamental messaging issue. “What we were saying wasn’t resonating,” Christie says. The attempt by pro-lifers to cast Issue 1 in terms of other concerns, such as those over parental rights and medicalized gender transition, did not measure up to the pro-abortion side’s portrayal of a vote as securing a Roe-style right to first-trimester abortion. Abortion proponents “had a clear message of ‘We need to protect these edge cases,’” says Adam Mathews, a state representative who remains committed to the pro-life cause. “With a lack of funding, with a lack of a clear message, we were not able to overcome that.”

The pro-life side suffered from lack of robust turnout among voters whose support it could have reasonably expected. Eighteen counties that voted for Donald Trump in 2020 also had majority support for Issue 1, according to the Cincinnati Enquirer. One third of self-identified weekly churchgoing Christian voters supported Issue 1, while 40 percent of that demographic statewide did not vote on the issue at all. Of self-identified weekly churchgoing Christians, 40 percent did not vote on the issue. There was a “failure of the body of Christ, of believers to show up to the polls to ensure that we voted against this particular amendment,” says Peter Range, senior fellow for strategic initiatives at Center for Christian Virtue, an advocacy organization in the state. But pro-abortion forces succeeded — misleadingly — at communicating the stakes to voters, including their own, and at setting the parameters for discussion of the issue.

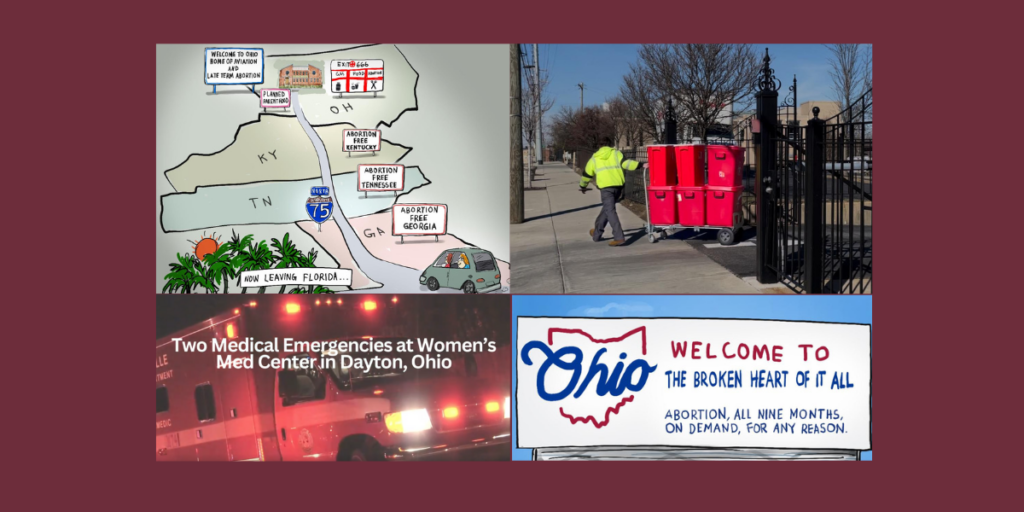

Because they prevailed, Issue 1 became part of Ohio’s notoriously amendment-prone constitution, and abortion is now permitted in Ohio at least to the point of fetal viability (around 24 to 26 weeks). Shortly before the Ohio March for Life, the state’s Department of Health released a report that gave a preview of what this will mean. It found that 22,000 abortions took place in Ohio in 2023, a 19 percent increase from the previous year. This in an abortion regime that permitted abortion up to 22 weeks, given judicial impediments to the establishment of protections for the unborn before the Issue 1 vote.

The now abortion-infused Ohio constitution will doubtless facilitate an increase in the number of abortions at least in the near future. The intentionally ambiguous language of the measure placed great weight on the up-for-debate words “burden,” to define what abortion restrictions the state could no longer permit, and “health,” to enumerate what could justify an abortion. Pro-lifers’ fear before the vote was that this capacious language would be used to gut existing protections for the unborn in the state, as had already been happening in neighboring Michigan. These fears are already being realized. The referendum is being used as a “sledgehammer,” as Range puts it, against protections for the unborn. The core provision of the state’s heartbeat law, which had been held up in the courts for much of the post-Dobbs period, has already gone. A judge recently struck down the state’s requirement that fetal remains be disposed of by cremation or interment.

These other rules are at risk, and in various states of litigation. Part of the heartbeat law, for example, required that a doctor notify a pregnant woman of the detection of a fetal heartbeat. The state’s 24-hour waiting period and ban on abortion via telemedicine remain in legal limbo. Much will depend on how these various cases proceed. “We recognize the people of the state voted for Issue 1 and that it’s part of the constitution,” says Ohio Attorney General Dave Yost. “That being said, it is a very, very broad amendment with little specificity. And there are certainly open questions, including the right of Ohio to regulate the practice of medicine for purposes of promoting the health and welfare of its citizens. So those arguments need to be made, and the state needs to be defended.”

Despite these circumstances, pro-lifers are not without political recourse. Issue 1 may be on the books, but elections do still matter. Last October, the stakes of then-impending elections for Ohio supreme court seats loomed large for attendees of the state’s March for Life. Three seats, two held by Democrats and one open, were up in the partisan contests. At the time, the court was split, four Republicans to three Democrats. In November, Republicans won all three, giving the state court a 6–1 Republican majority. This is no small victory: Current litigation over abortion restrictions will ultimately end up there.

There is also still hope in legislation. Mathews and other pro-life politicians remain committed to doing whatever they can under the amendment’s new regime. “Ohio’s constitution has been amended, but that should not allow us to shirk any responsibility to strengthen our families,” he says. Recently, he and a bipartisan group of state representatives introduced a bill to forbid “state-funded death” — that is, to prevent Ohio taxpayer money from funding not just abortion but also euthanasia and the death penalty. Other legislation under consideration would support new mothers, pregnancy centers, and, in general, a culture of life.

Such political activity will have to fight against a perennial temptation: to ignore pro-lifers and their cause. The Ohio march shares a purpose with its national equivalent: to ensure that pro-lifers won’t be ignored. “That’s our job as pro-life folks,” says Christie. “To say, no, we’re not going to go away.” In Ohio and elsewhere, the complications of a post-Roe world make this job more difficult — and more important.

But pro-lifers in Ohio do not see their task as only political. They also see a need to earn credibility in the eyes of Ohioans. The pro-life cause lost in November 2023, and will suffer going forward, in part because much of the public perceives it as callous, not compassionate. “When push came to shove and when we came to the public, does the average person in the United States believe the pro-life movement cared about the new life or what we can do for a woman who’s in need?” asks Will Kuehnle, associate director of social concerns at the Catholic Conference of Ohio (CCO). “The answer right now, the answer a year ago, is they just don’t.” Changing the hearts of the people will require pro-lifers to double down on the work they already do “walking with women in need,” as Brian Hickey, CCO’s executive director, puts it.

Such steps would be part of a broader campaign to revive the culture for life. It won’t be easy. In a sense, it brings pro-lifers back to the very beginning. “I kind of feel like the pro-life leaders must have felt back in 1973 when Roe v. Wade was first decided,” says Makra, “because I think in many ways, we have to start anew, to start building another consensus.” Ohio wasn’t the only place where the pro-life movement wasn’t fully prepared for the fall of Roe. And though that odious decision has been overturned, it will be harder to undo the culture of death it facilitated for nearly 50 years. That effort must take place culturally as well. “Maybe we’ve got to win the hearts and minds first, then change the laws,” says Marty, of Steubenville. That will take time. But younger generations are already taking up the cause. “There’s still hope,” says Andrew, one of his students. “That’s why we’re here.”

For now, the gut punch remains on the books. On that bright October day, a group of pro-abortion protesters stood on the edge of Capitol Square, within earshot of the assembled pro-lifers, chanting, “Ohio voted for abortion, Ohio supports abortion.” But Ohio’s pro-lifers are in this for the long haul. For the sake of the unborn who motivate them, and who ought to motivate us all, they must be. “We are not sprinters,” Peggy Hartshorn, chairwoman of the board of Heartbeat International, a pro-life pregnancy assistance network, told the marchers that day. “We are long-distance runners.”

Jack Butler is submissions editor at National Review Online, a 2023–2024 Leonine Fellow, and a 2022–2023 Robert Novak Journalism Fellow at the Fund for American Studies.