Abortion Activists Anticipate Pariah Status Under Mexico City Policy

By: Rebecca Oas, Ph.D., originally published January 2, 2025, C-Fam.org

WASHINGTON, D.C., January 3 (C-Fam) In the weeks leading up to the second inauguration of President Donald Trump, international abortion groups are ringing alarm bells about the anticipated return—and likely expansion—of a policy that would render them ineligible for U.S. funding unless they agree to stop promoting or providing abortions.

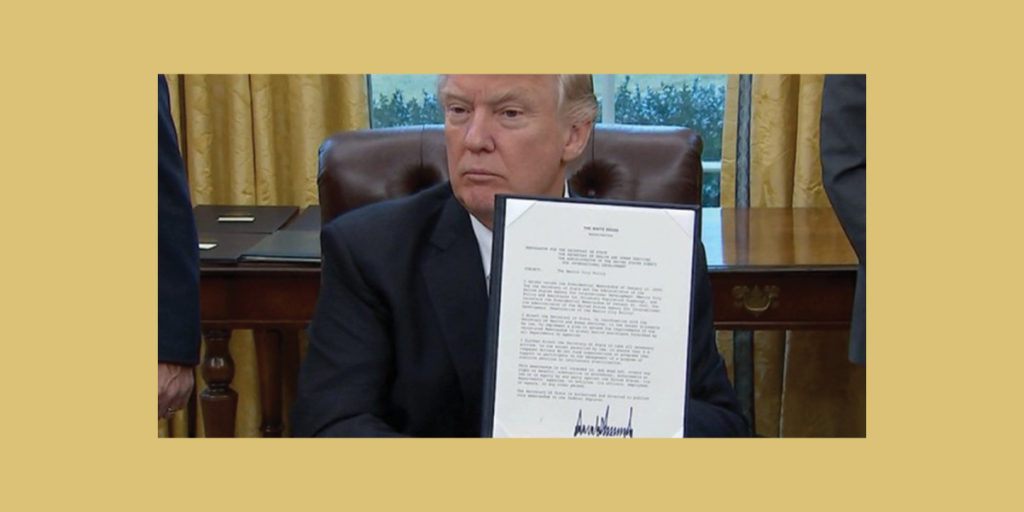

Introduced by President Ronald Reagan as the Mexico City Policy, the pro-life executive order has been in place under Republican presidents ever since, up to the first Trump administration. Trump expanded it to cover all global health assistance.

On a webinar hosted by Columbia University’s School of Public Health, Rachel Clement of Population Action International (PAI) noted that if Trump expanded the policy to include all foreign assistance, it could affect $51 billion in aid.

Under the previous Trump administration, relatively few foreign organizations refused to certify the policy, opting to forego U.S. funding, but these included the international abortion federations Planned Parenthood and MSI Reproductive Choices (formerly Marie Stopes).

Columbia University’s Sara Casey said that this effectively made the pro-abortion organizations into pariahs in the countries where they worked. “Certifying [organizations] were reluctant or unwilling to participate in meetings with organizations that provided abortion, even when those meetings were on another topic,” she said. “Non-certifying organizations sometimes found themselves excluded from meetings, even meetings that were convened by the ministry of health.”

Casey noted that there were a lot of “fractured collaborations” between organizations and “the breaking up of many longstanding or trusted partnerships” over the policy, as well as changes to referrals. “A certifying organization might stop referring clients for non-abortion care to an organization that declined to certify, so they might stop referring clients for family planning to a clinic that also provides abortions.”

Esther Kimani spoke on behalf of the Kenya-based Zamara Foundation, which is funded by Planned Parenthood and other pro-abortion donors. “Those that refused to comply really faced a lot of stigma, exclusion from joint efforts, and loss of partnerships in the community,” said Kimani. She added that the policy “provided an environment where anti-rights, anti-feminist movement, anti-gender movement, really thrived.”

According to Kimani, the policy also strengthened local pro-life movements in the region. “We say now, they have a bed within East Africa, and we’ve seen how they’ve really moved, having anti-choice frameworks that have been enacted in the past few years.”

Beth Schlachter of MSI positioned the Mexico City Policy within the broader scope of Trump’s pro-life foreign policy initiatives, including the Geneva Consensus Declaration, which calls for improved women’s health without abortion. The creators of the declaration have gone on to build a framework for optimal women’s health called Protego, providing a pathway to implementing the declaration in countries around the world.

“Many of the activities within this are quite standard and really promote women’s health,” admitted Schlachter. “It’s what’s not included in that: abortion, reproductive health and care for sex outside of marriage, and LGBTQI persons and their needs.”

Schlachter said that because MSI refused to certify the policy, 8 million women went unserved as a result. “We were able to document that about 20,000 women died in maternal health situations.” She blamed the policy, not MSI’s prioritization of abortion over U.S. funding, for those deaths.

Nabeeha Hutchins, the president of PAI had a pessimistic view of the funding landscape for international abortion groups. “Our funding approach is not aligned with what the opposition is doing. The opposition funds long-term…we are having to respond with the short view.”

“Donors are leaving, champions are leaving and moving to other sectors.”

Rebecca Oas is the Director of Research for the Center for Family and Human Rights (C-Fam) in Washington, D.C