What Does Another Trump Presidency Mean for the Pro-Life Movement?

By: Patrick T. Brown, originally published November 17, 2024, The Public Discourse

Trump’s reelection provides reason for pro-lifers to be cautiously relieved, though still apprehensive.

Team Life can look at the recent elections with something of a sigh of relief. The worst was averted.

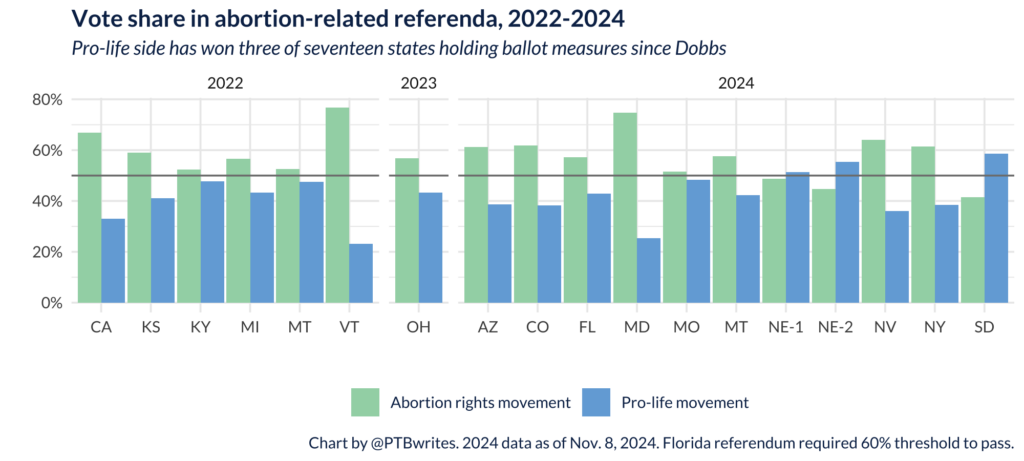

After seven straight losses in ballot measures, the pro-life movement finally racked up some victories, defeating abortion rights referenda in Florida, Nebraska, and South Dakota. West Virginia narrowly approved a constitutional amendment to bar assisted suicide from the state. A slew of pro-life governors and senators were reelected in solid red states.

But the bag was decidedly mixed. Five states with large pro-choice majorities reified their commitment to abortion on demand, including Colorado, which opened the door to taxpayer funding for abortion at any point during pregnancy. Arizona, a state with a longstanding libertarian streak, opted to eschew the fifteen-week limit the legislature passed earlier this year, adopting a California-style “reproductive rights” amendment. And Missouri, a relatively religious state, voted down their near-total abortion ban in favor of an amendment that legalizes the procedure until birth.

There have now been eighteen statewide referenda on abortion since Dobbs; not enough for any real statistical power, but enough to give us some general information. And the picture isn’t very attractive for pro-lifers.

In the races the pro-life side has lost, the margin between those efforts and the pro-choice side of the ledger averages 17.8 points, including the fifty-point whoppers in Vermont and Maryland. The closest calls came in Missouri and Kentucky, where the defeats were each by less than five percentage points; a 2022 Montana referendum about whether to provide care to an infant born alive as a result of a botched abortion was similarly narrow. Other than that, the tale of the tape is grim.

The silver lining, such as it is, is that the popular referenda strategy will soon begin to run out of steam for the abortion rights side. Per the New York Times, there are just three more states that restrict abortion with voter-initiated referenda: Arkansas (where a clerical error left an amendment off this fall’s ballot), North Dakota, and Oklahoma. The remaining pro-life laws on the books are in states without easy ways for voters to strike them down, suggesting an uneasy stalemate could soon be within reach.

It’s not inconceivable that abortion rights forces might regroup and tackle Florida again, maybe this time with something slightly more measured, say, a twenty-week gestational limit, in hopes of getting over the required 60 percent threshold to change the state constitution. Turnabout is fair play; in four or eight years, pro-life funders should commit to devoting the millions of dollars necessary to reverse the sweeping abortion liberalization in Missouri. An amendment that bans abortion at six or eight weeks with clear, common-sense exceptions would stand an excellent chance of making it over the top.

All told, the ballot box remains perilous for the cause of life. There will be few profiles in political courage, like the one offered by Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, who put his political future on the line to give the state’s heartbeat bill a fighting chance. For that, he deserves the pro-life movement’s respect and gratitude. We will be continually outgunned in donations and media coverage. But last week proved that, under the right circumstances, supporting life in state referenda is not an automatic loser; that alone is reason to hope.

This brings us to how efforts to protect life fit into the game of national politics. The reelection of former President Donald Trump provides reason for pro-lifers to be cautiously relieved, though still apprehensive. If Trump had lost, both his campaign team and progressives would have laid the defeat at the feet of Dobbs, as in the most recent midterms.

As it turns out, the abortion issue didn’t save Democrats nearly as much as advertised in 2022, as The Dispatch’s John McCormack recently recapped. Indeed, the impact of abortion on the 2024 presidential election seems to have been a dog-who-didn’t-bark story, at least until we get more reliable information than exit polls. But the issue would have been an easy scapegoat; as such, another bullet dodged.

Of course, during the campaign, President Trump created as much distance as politically possible between himself and the pro-life movement. Disavowing a federal abortion ban was smart, and arguably constitutionally correct. Talking up common-sense exceptions, like for rape or incest is, or should be, standard practice in a post-Dobbs era. But taking pro-life language out of the GOP platform was cowardly, riling up those who believe in the sanctity of life by eschewing action on medication abortion or promising taxpayer dollars for embryo destruction. And sandbagging pro-life states by calling their laws to protect unborn life “terrible” was a bridge too far, and then some.

Pro-lifers can and should make the argument that the size and breadth of Trump’s victory at the national level suggests that some of this distancing was overkill. It seems unlikely that his various fertility-related campaign promises could have moved many votes, even on the margin. Being smart about the politics of life doesn’t have to mean being craven.

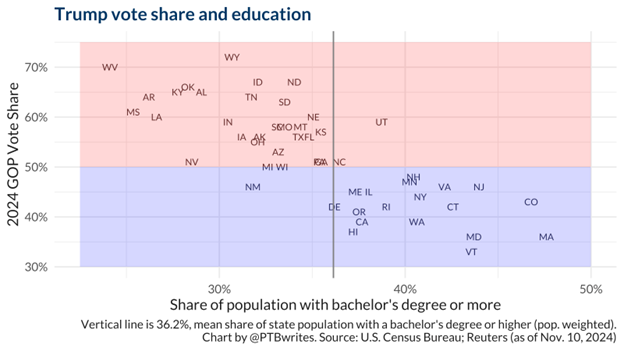

But it also means understanding that the new, working-class coalition powering the GOP is less interested in the social conservative causes that have traditionally had a seat at the table in Republican politics. As I write, they are still counting votes on the West Coast, so any election analysis is bound to be somewhat provisional. But even with that caveat we can see in this chart the simple story of what happened in 2024 in one, clear image:

Essentially, if your state had a higher-than-average share of residents with a bachelor’s degree or more, your state voted for Vice-President Kamala Harris. If it had a below-average share of adults over age twenty-five with a college degree, it voted for former (and future) President Trump. That’s it; that’s the election. (Utah and New Mexico, due to their distinctive demographics, are the two outliers in the otherwise clean break; North Carolina has been the definition of a swing state these past three elections.)

This is because educational polarization is becoming the hallmark of our electorate; college-educated voters, predominantly white, are migrating leftwards, while Americans without college degrees, especially Hispanic voters, are forming the cross-racial working-class coalition foretold by analysts like my Ethics and Public Policy Center colleague Henry Olsen, American Compass’ Oren Cass, and Echelon Insights’ Patrick Ruffini.

This may very well augur a Republican Party that pays more attention to the economic and cultural concerns of working-class Americans—and it should. But religious attendance and adherence are in steepest decline among Americans without a college degree, meaning the new coalition on the Right—call them “cultural” conservatives, rather than “social” ones—are motivated less by traditional religious concerns.

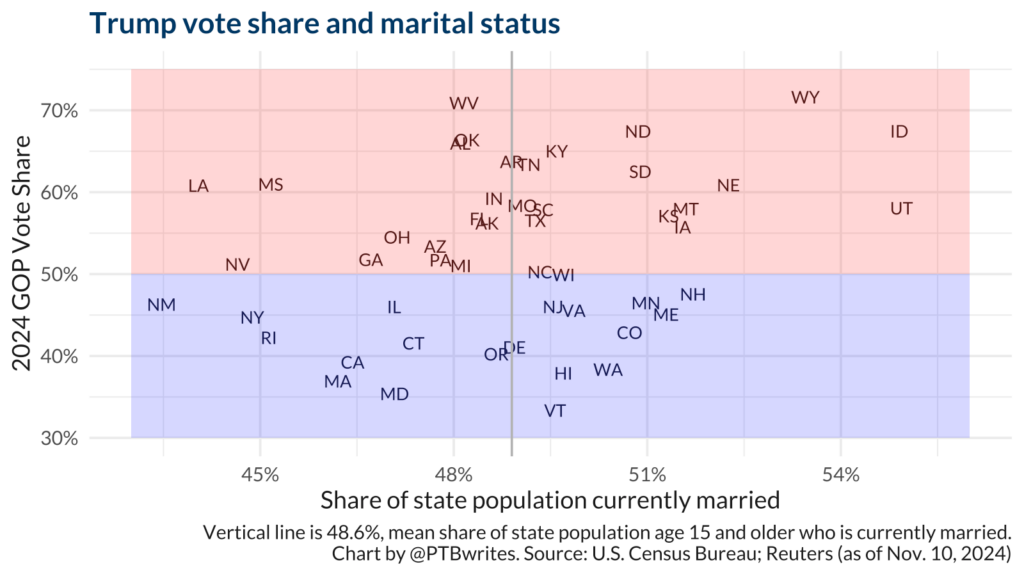

Breaking down President-elect Trump’s support by the level of religious adherence in a given state (not shown) shows how states with above-average shares of religious attendees were disproportionately likely to vote for the former President. But he also racks up big numbers with relatively non-religious states like Montana, New Hampshire, and the decisive battlegrounds of Nevada and Michigan. Another way to look at this dynamic is to isolate marital status. The share of adults ages fifteen and up who are currently married is only weakly predictive of President-elect Trump’s 2024 vote share because of the well-known decline in marriage among Americans without a college degree.

President Trump’s electric connection to his working-class base likely succeeds, at least in part, because he avoids the “preachy” connotations of the religious Right. He has appeared in Playboy more times than he’s criticized pornography. He endorsed another Florida amendment to legalize marijuana in the state (which, thankfully, failed). He is, as Protestant intellectual Aaron Renn wrote, the first President of a post-Christian America.

None of this is to say that a Trump administration with the right people in the right places can’t make a meaningful positive difference, not least in halting some of the Biden administration’s egregious overreaches. There are exciting opportunities to advance broadly pro-family goals. But at the same time, pro-life and pro-family conservatives should keep their eyes open about who they are dealing with. Trump’s stamp on the Party, and on the conservative movement, remain a long-term liability. Those who believe in the sanctity of marriage and the defense of unborn human life will have plenty to work on with a second Trump administration. But they should not lose their willingness or ability to call it as they see it.

One example of how this can work in practice happened in August, when Trump gave an interview to NBC News suggesting the Florida referendum mentioned above was directionally correct. The “six-week [ban] is too short,” he said in late August, saying he favored “more time.” When asked explicitly by a reporter if he would vote in favor of the amendment, thereby permitting abortion until the point of viability, Trump indicated approval. “I’m going to be voting that we need more than six weeks.”

The outrage was swift and condemnation severe. Groups that had partnered with the Trump administration during his first term in office worked publicly and behind the scenes to get the Trump team to understand the depth of this betrayal. And, to his credit, the former President backtracked, telling Fox News the next day that he would be voting no, and sought to avoid discussion of the amendment throughout the rest of the campaign.

Trump won the Sunshine State by thirteen percentage points, and the abortion amendment fell three percentage points short of passage; his grudging about-face may have helped make the difference. And it showed that the relationship between pro-life groups and the Trump campaign need not be one-sided; if a Trump administration proposes policies that run afoul of an authentic understanding of human dignity, pro-life activists should be prepared to speak out.

The reelection of Donald Trump comes at a hinge point for the socially conservative wing of the Republican coalition. Enough ink has been spilled on the unlikely fact that he, of all the hypothetical figures on the national stage, was the one to deliver the Supreme Court justices who overturned Roe. With Roe gone, the field of battle has moved squarely from the courtroom to ballot boxes and state houses across the country. The pro-life movement needs to find policy measures to give mothers, babies, and families meaningful support, as Emma Green recently discussed in The New Yorker.

This requires taking our Achilles’ heel seriously. Turning to legal arguments to win cultural battles will not be sustainable over the long term; voters in the middle need to be convinced that we understand what women considering abortion are going through and that we are committed to meeting them where they are.

As Amber Lapp wrote for the Institute for Family Studies, the pro-life movement faces a deficit of trust, even among the women it’s trying to help. She talked to Leanne, a twenty-something waitress who had struggled with substance abuse. Leanne said, “I’m pro-life, but I’m also pro women’s choice; I want to make sure that it’s the woman making the choice. Is she getting the services [she needs]? What kind of support does she have?”

A policy agenda that responds to those concerns won’t inoculate the pro-life movement from future political losses. But it needs to be a major part of our efforts going forward on a moral level, as well as the level of practical politics. As the conservative coalition slowly slides towards a post-religious orientation, and as progressive politicians become ever more committed to removing all barriers on abortion at any point in pregnancy, prioritizing legislative efforts to expand support for families will become a political necessity.

Figuring out how to advance the cause of justice for the unborn with the reality of a secularizing America will require heavy long-term thinking. But because it avoided the worst-case scenario in the 2024 election, the pro-life movement may well have meaningful opportunities to improve our response to women and families over the course of the second Trump administration. We shouldn’t miss our chance.

Patrick T. Brown is a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, where he writes on family policy.